NEAR Protocol

For beginners, it’s always better to start with documentation, and NEAR has an excellent one. Here, we only focus on basic concepts necessary to understand later chapters, so an entire guideline can be understood without prior NEAR knowledge.

Accounts & Transactions

NEAR's account system is very powerful and differs substantially from other blockchains, like Bitcoin or Ethereum. Instead of identifying users by their public/private key pairs, it defines accounts as first-class entities. This has a few important implications: Instead of identifying users by their public/private key pairs, it defines accounts as first-class entities. This has a few important implications:

- Instead of public keys, users can use readable account names.

- Multiple key pairs with different permissions can be used. This provides a better security model for users, since loss of one key pair doesn’t compromise an entire account and has a quite limited impact. This provides a better security model for users, since loss of one key pair doesn’t compromise an entire account and has a quite limited impact.

- Hierarchical accounts structure is supported. Hierarchical accounts structure is supported. This is useful if we want to manage multiple smart contracts under one parent account.

- Accounts/public keys are created using transactions, since they are stored on the blockchain.

More information on NEAR accounts can be found in the docs.

But an account by itself won’t get us anywhere, its transactions that make things happen. In NEAR, we have only one transaction type, but the transaction itself may have different actions included. For most practical purposes, transactions will have a single action included, so for simplicity we’ll use “action” and “transaction” terms interchangeably further down the road. Each transaction always has sender and receiver accounts (and it is cryptographically signed by the sender’s key). The following transaction (action) types are supported: In NEAR, we have only one transaction type, but the transaction itself may have different actions included. For most practical purposes, transactions will have a single action included, so for simplicity we’ll use “action” and “transaction” terms interchangeably further down the road. Each transaction always has sender and receiver accounts (and it is cryptographically signed by the sender’s key). The following transaction (action) types are supported:

- CreateAccount/DeleteAccount, AddKey/DeleteKey - accounts and key management transactions.

- Transfer - send NEAR tokens from one account to another. The basic command of any blockchain. The basic command of any blockchain.

- Stake - needed to become a validator in a Proof-of-Stake blockchain network. We won’t touch this topic in this guideline, more information can be found here. We won’t touch this topic in this guideline, more information can be found here.

- DeployContract - deploy a smart contract to a given account. An important thing to remember - one account can hold only one contract, so the contract is uniquely identified by the account name. If we issue this transaction to an account which already has a deployed contract, a contract update will be triggered. An important thing to remember - one account can hold only one contract, so the contract is uniquely identified by the account name. If we issue this transaction to an account which already has a deployed contract, a contract update will be triggered.

- FunctionCall - the most important action on the blockchain, it allows us to call a function of a smart contract.

Smart Contracts on NEAR are written in Rust or JavaScript, and compiled into WebAssembly. Each contract has one or more methods that can be called via a FunctionCall transaction. Methods may have arguments provided, so each smart contract call includes the following payload: account id, method name, and arguments. Each contract has one or more methods that can be called via a FunctionCall transaction. Methods may have arguments provided, so each smart contract call includes the following payload: account id, method name, and arguments.

There are 2 ways to call a method on a smart contract:

- Issue a FunctionCall transaction. Issue a FunctionCall transaction. This will create a new transaction on a blockchain which may modify a contract state.

- Make a smart contract view call. Make a smart contract view call. NEAR blockchain RPC nodes provide a special API that allow execution of methods that do not modify contract state (readonly methods).

The second method should always be used whenever possible since it doesn’t incur any transaction cost (of course, there is some cost of running a node, but it’s still much cheaper than a transaction; public nodes are available which can be used free of charge). Also, since there’s no transactions, we don’t need an account to make a view call, which is quite useful for building client-side applications Also, since there’s no transactions, we don’t need an account to make a view call, which is quite useful for building client-side applications

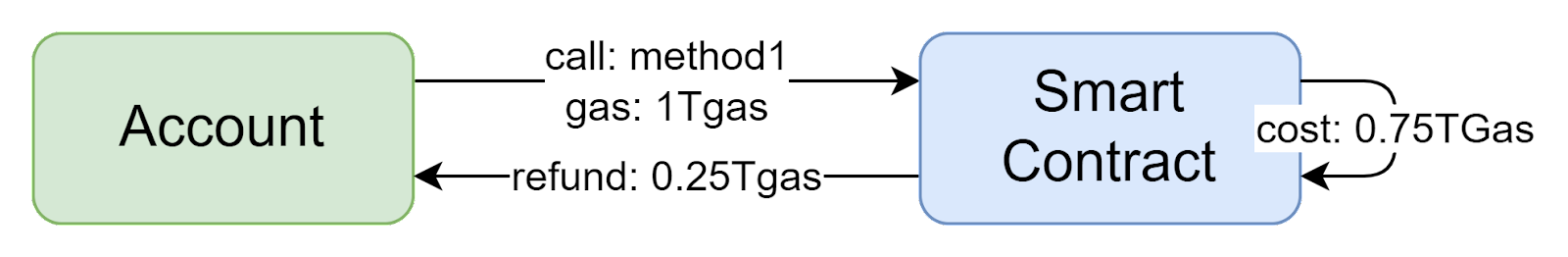

Gas and Storage

As we already discussed, users should pay computational costs for each transaction. This cost is called “gas” and is measured in gas units (this is an established term in the blockchain world). Each time a transaction is posted, an amount of gas is attached to it to cover the cost. For simple transactions, gas can be calculated ahead of time to attach an exact amount. For FunctionCall transactions, however, exact cost is impossible to automatically calculate beforehand, so the usual approach is to attach a large enough amount of gas to cover the cost, and any excess will get automatically refunded.

But why do we need separate gas units, why not just pay directly with NEAR tokens? It’s necessary to accommodate for changing infrastructure costs - as the network evolves over time, cost of gas units may change, but the amount of gas required for a transaction will remain constant. It’s necessary to accommodate for changing infrastructure costs - as the network evolves over time, cost of gas units may change, but the amount of gas required for a transaction will remain constant.

However, computational cost is not everything - most smart contracts also need storage. The storage cost in NEAR is quite different from gas. First of all, it’s not cheap - while gas is very cheap and its cost will be almost unnoticeable by the users, storage is very expensive. As a consequence, the storage budget should be carefully calculated and only necessary data stored on the blockchain. Any auxiliary data (that is not necessary to the contract operations) should be stored off-chain (possible solutions will be covered in later chapters). The second important difference - storage is not bought, but leased (in NEAR, it’s called staking). When a smart contract wants to store some data, storage cost is computed and the appropriate amount of NEAR tokens is “locked” on the account. When data is removed, tokens are unlocked. And unlike gas, these tokens are locked on the smart contract’s account, so the user doesn’t directly pay for it.

But what if we want users to pay for the storage (or just pay some fee for using a smart contract)? So far, the only way we’ve seen to transfer a token is a Transfer transaction. It turns out, a FunctionCall transaction also allows us to transfer tokens alongside the call (this is called a deposit). Smart Contracts can verify that an appropriate amount of tokens has been attached, and refuse to perform any actions if there’s not enough (and refund any excess of tokens attached). So far, the only way we’ve seen to transfer a token is a Transfer transaction. It turns out, a FunctionCall transaction also allows us to transfer tokens alongside the call (this is called a deposit). Smart Contracts can verify that an appropriate amount of tokens has been attached, and refuse to perform any actions if there’s not enough (and refund any excess of tokens attached).

In combination, gas fee and deposit attachments enable creation of contracts that need zero cost from developers to support and can live on blockchain forever. Even more, 30% of gas fees spent on the contract execution will go to a contract’s account itself (read more here), so just by being used it will bring some income. To be fair, due to the cheap gas cost this will make a significant impact only for most popular and often-called contracts, but it’s nice to have such an option nonetheless. Even more, 30% of gas fees spent on the contract execution will go to a contract’s account itself (read more here), so just by being used it will bring some income. To be fair, due to the cheap gas cost this will make a significant impact only for most popular and often-called contracts, but it’s nice to have such an option nonetheless.

One last gotcha about storage - remember that smart contracts themselves are also just a code stored on a blockchain, so a DeployContract transaction will also incur storage fees. Since smart contracts code can be quite big, it’s important to optimize their size. A few tips on this: Since smart contracts code can be quite big, it’s important to optimize their size. A few tips on this:

- Don’t build Rust code on Windows, it produces quite big output. Use WSL or build on other OSes. Use WSL or build on other OSes.

- Optimize smart contracts code for size - more info here

More details on the storage model can be found in the docs.

Clients Integration

So far, we’ve discussed how to call smart contracts in a client-agnostic way. So far, we’ve discussed how to call smart contracts in a client-agnostic way. However, in the real world, calls we’ll be performed from a client side - like web, mobile or a desktop application.

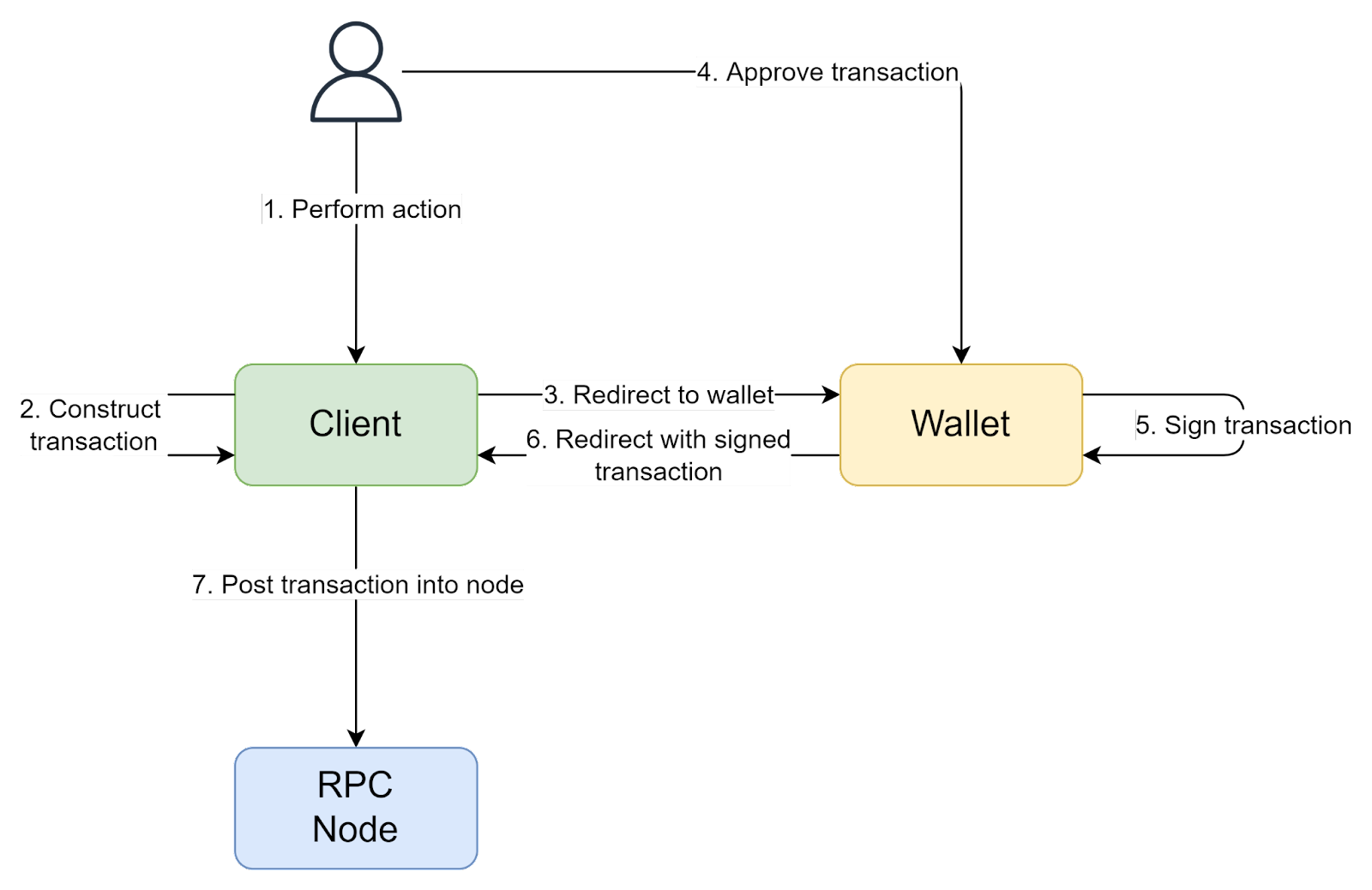

As we’ve learned from previous chapters, each transaction should be signed using a key. And since keys are managed by a wallet, each application should integrate with it. At the time of this writing, there’s only one officially supported NEAR Wallet. It is a web application, so integration happens using HTTP redirects. This is relatively straightforward to do in web applications (JavaScript SDK is available), but for mobile or desktop applications it may require deep linking or other more advanced approaches.

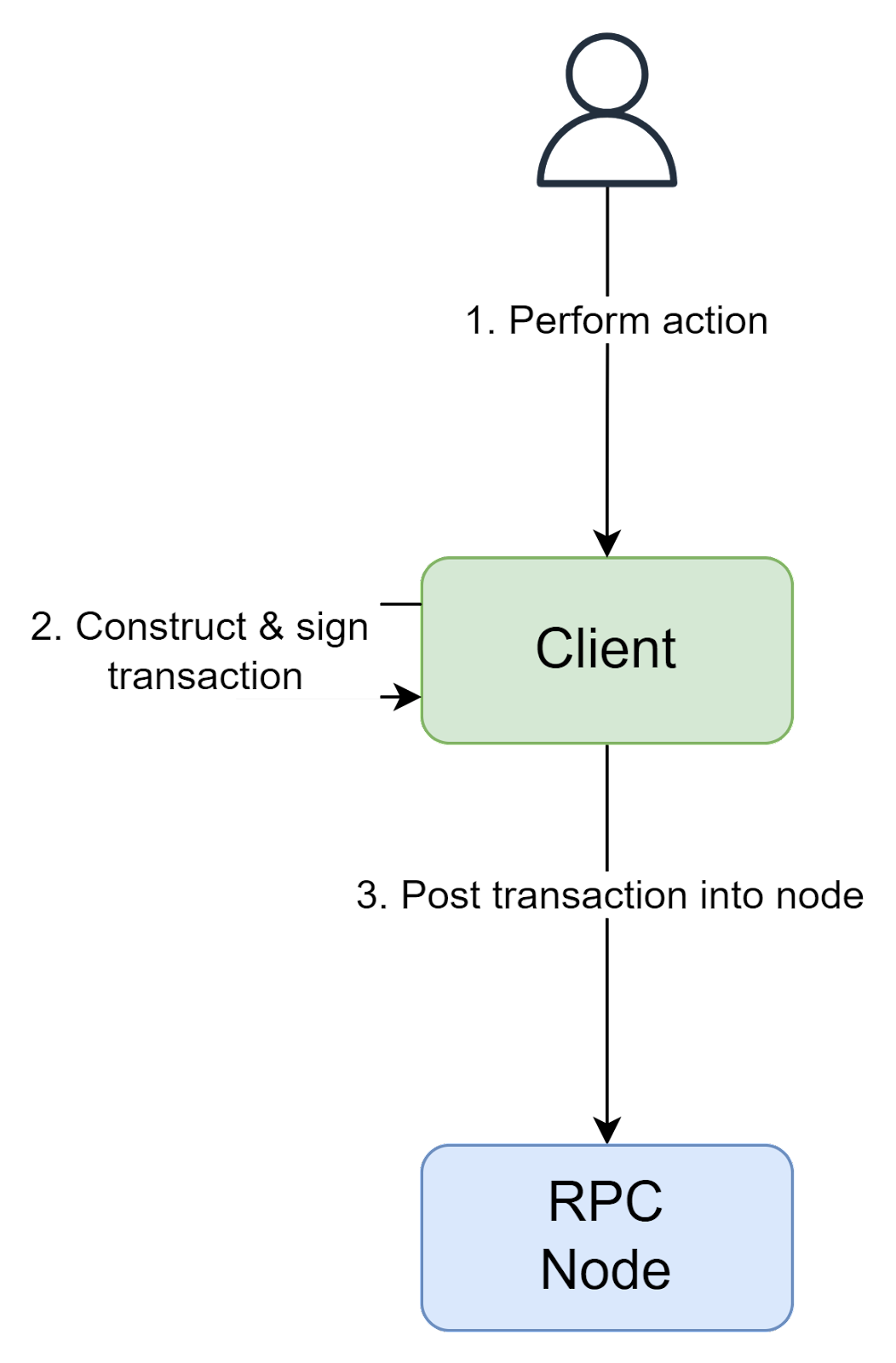

The general flow for transactions signing looks like this:

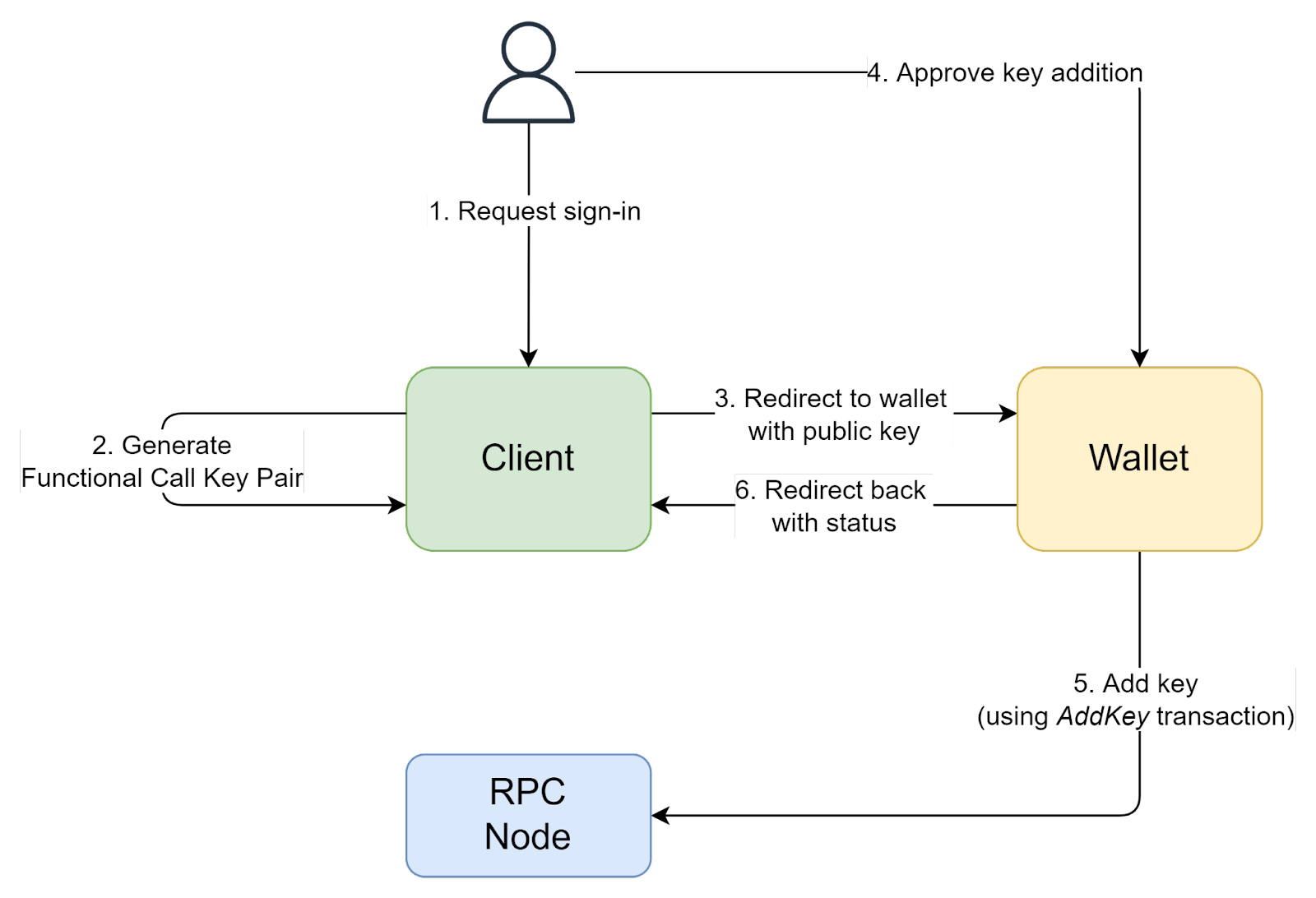

Each time we want to post a transaction, the client redirects the user to a wallet, where the transaction is approved and wallet returns a signed transaction back to the client (via redirect). This is a quite secure way of signing, since the private key is not exposed to the client, but constant redirects might quickly get annoying for users, especially if we just want to call smart contract functions that incur only small gas fees. That’s why NEAR introduced two types of access keys - full keys and functional call keys. Full access keys, as the name implies, can be used to sign any types of transactions. Functional call keys, on the other hand, aim to solve this UX problem. They are tied to a specific contract, and have a budget for gas fees. Each time we want to post a transaction, the client redirects the user to a wallet, where the transaction is approved and wallet returns a signed transaction back to the client (via redirect). This is a quite secure way of signing, since the private key is not exposed to the client, but constant redirects might quickly get annoying for users, especially if we just want to call smart contract functions that incur only small gas fees. That’s why NEAR introduced two types of access keys - full keys and functional call keys. Full access keys, as the name implies, can be used to sign any types of transactions. Functional call keys, on the other hand, aim to solve this UX problem. They are tied to a specific contract, and have a budget for gas fees. Such a key can’t be used to sign transactions that transfers NEAR tokens (payable transactions), and can only be used to cover gas fees, that’s why it’s not so security-critical and can be stored on the client. Because of this, we can create a simplified signing flow for non-payable transactions. First of all, a login flow to obtain a Functional Call key is used. Because of this, we can create a simplified signing flow for non-payable transactions. First of all, a login flow to obtain a Functional Call key is used.

The client generates a new key pair and asks a wallet to add it as a functional call key for a given contract. After this, a login session is established and considered alive until the client has the generated key pair. To provide the best user experience usage of both keys is combined - type of signing is determined based on a transaction type (payable or non-payable). In case of a payable transaction, flow with wallet redirection is used, otherwise simplified local signing flow (using a stored function call key) is applied: After this, a login session is established and considered alive until the client has the generated key pair. To provide the best user experience usage of both keys is combined - type of signing is determined based on a transaction type (payable or non-payable). In case of a payable transaction, flow with wallet redirection is used, otherwise simplified local signing flow (using a stored function call key) is applied:

It’s important to note that it’s possible to generate a Full Access key using the same key addition flow as for the Functional Call key, but this is very dangerous since compromise of such key will give full control over an account. Applications that want to work with Full Key directly should be designed with extreme care, especially in the matters of security. Applications that want to work with Full Key directly should be designed with extreme care, especially in the matters of security.

Cross-contracts calls

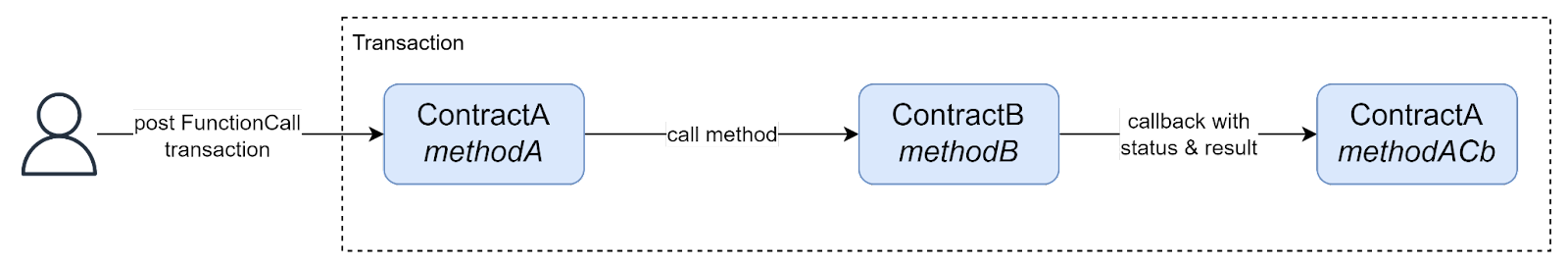

Throughout this section, we’ve discussed how to call a smart contract from a client. But a single smart contract can only take us so far. The true power is achieved when smart contracts are working in concert and communicating with each other. To achieve this, NEAR provides cross-contract calls functionality, which allows one contract to call methods from another contract. The general flow looks like this:

Looks simple enough, but there are few gotchas:

- In order to provide a call status (success or failure) and a return value to the calling contract, a callback method should be called, so there’s no single activation of ContractA. Instead, an entry method is called first by the user, and then a callback is invoked in response to cross-contract call completion. Instead, an entry method is called first by the user, and then a callback is invoked in response to cross-contract call completion.

- Transaction status is determined by the success or failure of a first function call. For example, if a ContractB.methodB or ContractA.methodACb call fails, the transaction will still be considered successful. This means that to ensure proper rollbacks in case of expected failures, custom rollback code must be written in the ContractA.methodACb, and the callback method itself must not fail at all. Otherwise, smart contract state might be left inconsistent.

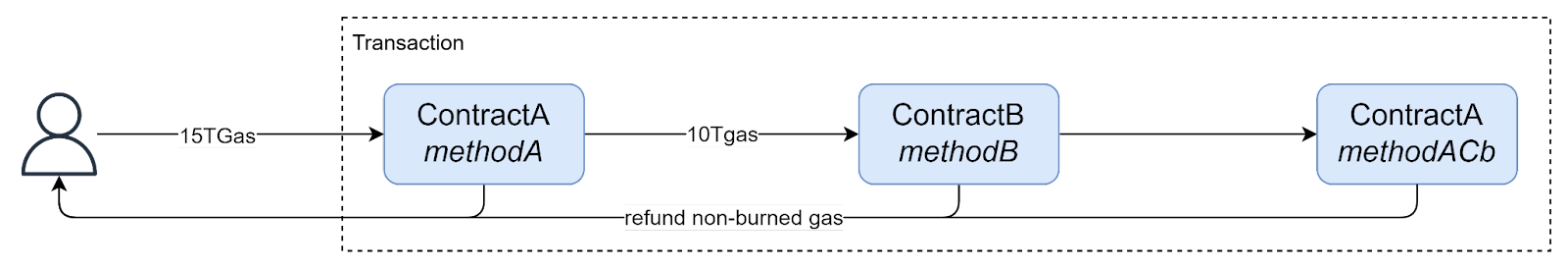

- Cross-contract calls must have gas attached by the calling contract. Total available gas is attached to a transaction by a calling user, and distributed inside the call chain by contracts. For example, if 15TGas are attached by the user, ContractA may reserve 5TGas for itself and pass the rest to ContractB. All unspent gas will be refunded back to the user. Total available gas is attached to a transaction by a calling user, and distributed inside the call chain by contracts. For example, if 15TGas are attached by the user, ContractA may reserve 5TGas for itself and pass the rest to ContractB. All unspent gas will be refunded back to the user.

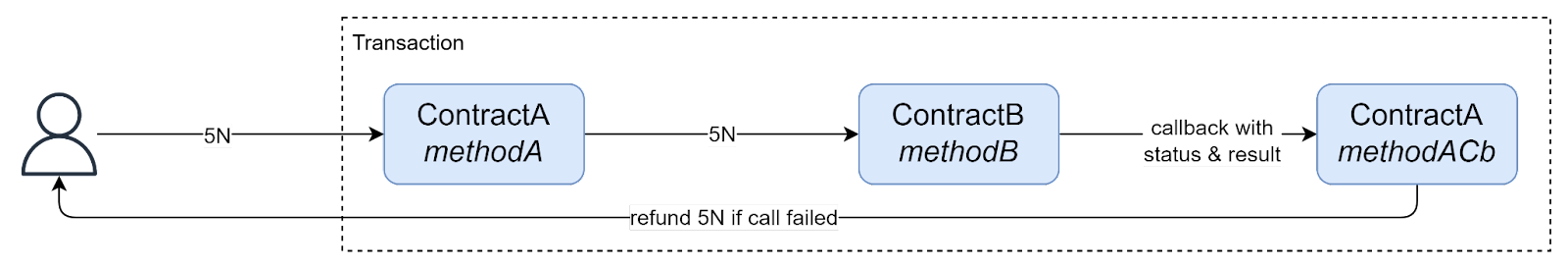

- NEAR tokens can also be attached to cross contract calls, but they work differently from the gas. Attached deposit is taken directly from the predecessor account. It means even if a user hasn’t attached any deposit, a contract still can attach tokens, which will be taken from its account. Also, since cross-contract call failure doesn’t mean transaction failure, there are no automatic refunds. All refunds should be done explicitly in the rollback code.

A few notes on failure modes - since smart contracts run on a decentralized environment, which means they are executed on multiple machines and there is no single point of failure, they won’t fail because of environment issues (e.g. because a machine suddenly lost power or network connectivity). The only possible failures come from the code itself, so they can be predicted and proper failover code added. The only possible failures come from the code itself, so they can be predicted and proper failover code added.

In general, cross-contract call graphs can be quite complex (one contract may call multiple contracts and even perform some conditional calls selection). In general, cross-contract call graphs can be quite complex (one contract may call multiple contracts and even perform some conditional calls selection). The only limiting factor is the amount of gas attached, and there is a hard cap defined by the network of how many gas transactions may have (this is necessary to prevent any kind of DoS attacks on the Network and keep contracts complexity within reasonable bounds).

Data Structures, Indexers and Events

We’ve already discussed the storage model on NEAR, but only in abstract terms, without bringing the exact structure, so it’s time to dive a bit deeper.

Natively, NEAR smart contracts store data as key-value pairs. This is quite limiting, since even simplest applications usually need more advanced data structures. To help in development, NEAR provides SDK for smart contracts, which includes data structures like vectors, sets and maps. While they are very useful, it’s important to remember a few things about them:

- Ultimately, they are stored as binary values, which means it takes some gas to serialize and deserialize them. Also, different operations cost different amounts of gas (complexity table). Because of this, careful choice of data structures is very important. Moving to a different data structure later will not be easy and would probably require data migration.

- While very useful, vectors, maps and sets won’t match the flexibility and power of classical relational databases. Even implementations of simple filtering and searching might be quite complex and require a lot of gas to execute, especially if multiple entities with relations between them are involved. Even implementations of simple filtering and searching might be quite complex and require a lot of gas to execute, especially if multiple entities with relations between them are involved.

- They are limited to a single contract. They are limited to a single contract. If data from multiple contracts is required, aggregation should be performed using cross-contract calls or on a client side, which is quite expensive in terms of gas and time.

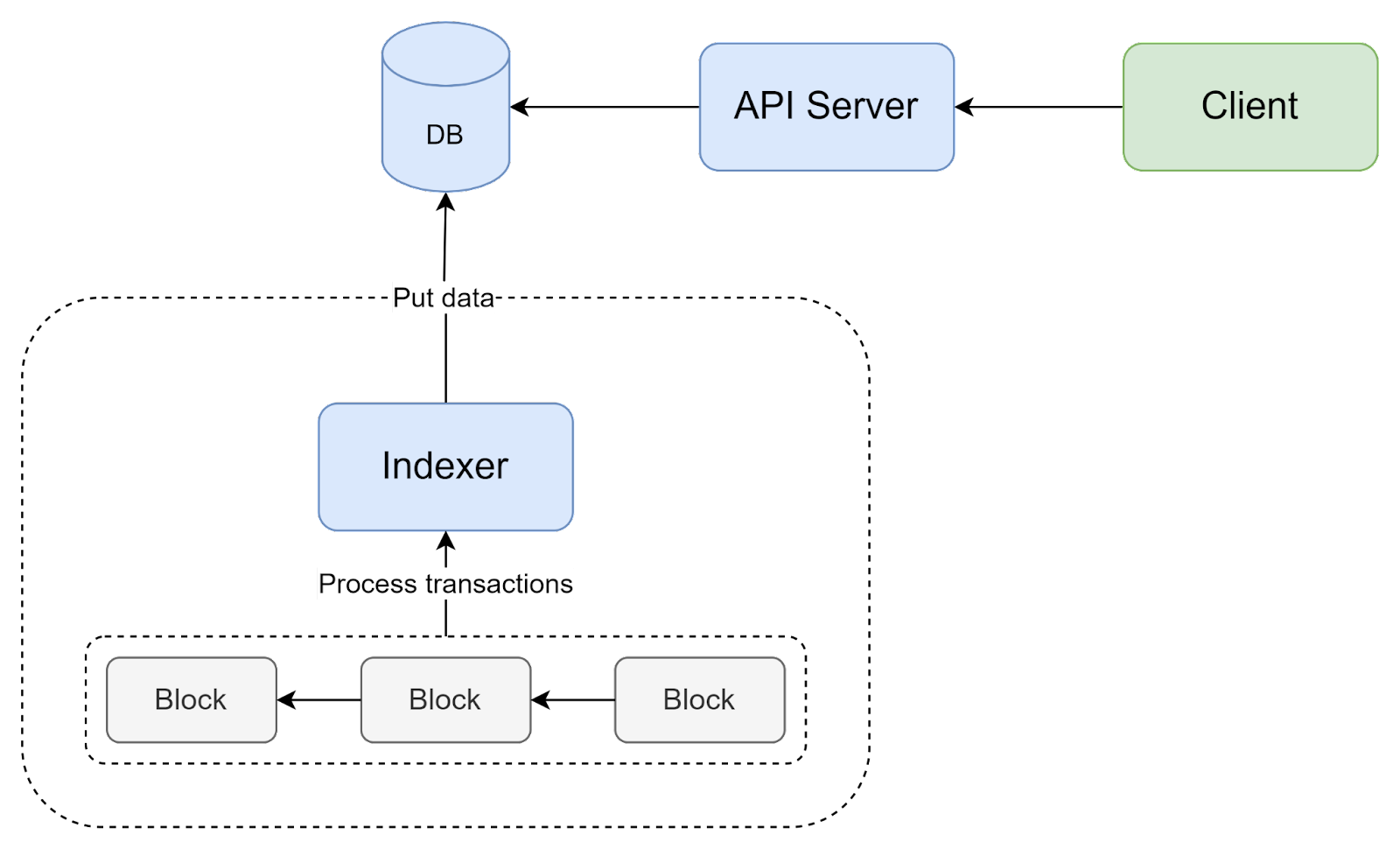

To support more complex data retrieval scenarios, smart contract data should be put in a more appropriate store, like a relational database. Indexers are used to achieve this. In a nutshell, indexer is just a special kind of blockchain node that processes incoming transactions and puts relevant data into a database. Collected data can be exposed to a client using a simple API server (e.g. REST or GraphQL).

In order to simplify creation of indexers, NEAR Indexer Framework has been created. However, even with a framework available, extracting data from a transaction may not be an easy task, since each smart contract has its unique structure and data storage model. To simplify this process, smart contracts can write structured information about outcome into the logs (e.g. in the JSON format). Each smart contract can use its own format for such logs, but the general format has been standardized as Events.

Such architecture is very similar to Event Sourcing, where blockchain stores events (transactions), and they are materialized to a relational database using an indexer. This means the same drawbacks also apply. For instance, a client should be designed to accommodate indexing delay, which may take a few seconds. This means the same drawbacks also apply. For instance, a client should be designed to accommodate indexing delay, which may take a few seconds.

As an alternative to building your own indexer with a database and an API server, The Graph can be used instead, which currently has NEAR support in beta. It works using the Indexer-as-a-Service model, and even has decentralized indexing implementation. It works using the Indexer-as-a-Service model, and even has decentralized indexing implementation.

Development tools

By now, we should be familiar with necessary concepts to start developing WEB 3.0 applications, so let’s explore the development tools available.

First of all, we need a development and testing environment. Of course, we could theoretically perform development and testing on the main blockchain network, but this would not be cheap. For this reason, NEAR provides several networks that can be used during development:

- testnet - public NEAR network which is identical to mainnet and can be used for free.

- localnet - you can deploy your personal NEAR network on your own environment. Because it’s owned by you, data and code can be kept private during development. More info on how you can run your own node can be found here. localnet - you can deploy your personal NEAR network on your own environment. Because it’s owned by you, data and code can be kept private during development. More info on how you can run your own node can be found here. Alternatively, you can bootstrap an entire testing infrastructure in Docker on your local machine using Kurtosis - guide is here.

- workspaces - you can start your own local network to perform e2e testing. More info here. More info here.

Once we’ve chosen a network to use, we need a way to interact with it. Of course, transactions can be constructed manually and posted into node’s API. But this is tedious and isn’t fun at all. That’s why, NEAR provides a CLI which automates all of the necessary actions. It can be used locally for development purposes or on build machines for CI/CD scenarios.

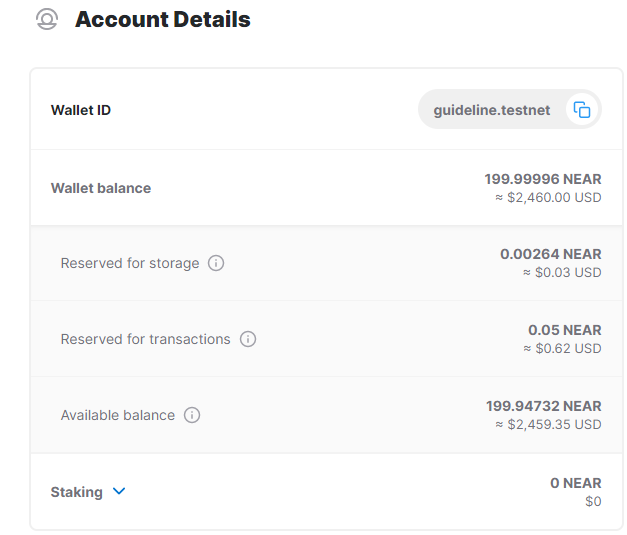

In order to manage accounts on the NEAR network, Wallet can be used. It can show an effective account balance and active keys. It can show an effective account balance and active keys.

On the image above, “Reserved for storage” are tokens locked by a smart contract to cover current storage requirements, and “Reserved for transactions” represents the amount of tokens locked to cover gas cost by Functional Call keys. Currently, there’s no UI to connect sub-accounts into a wallet. Instead, they should be imported via a specially constructed direct link: Currently, there’s no UI to connect sub-accounts into a wallet. Instead, they should be imported via a specially constructed direct link:

https://testnet.mynearwallet.com/auto-import-secret-key#YOUR_ACCOUNT_ID/YOUR_PRIVATE_KEY

(you should provide a private key of a full access key for the account in question, so make sure this link is used securely).

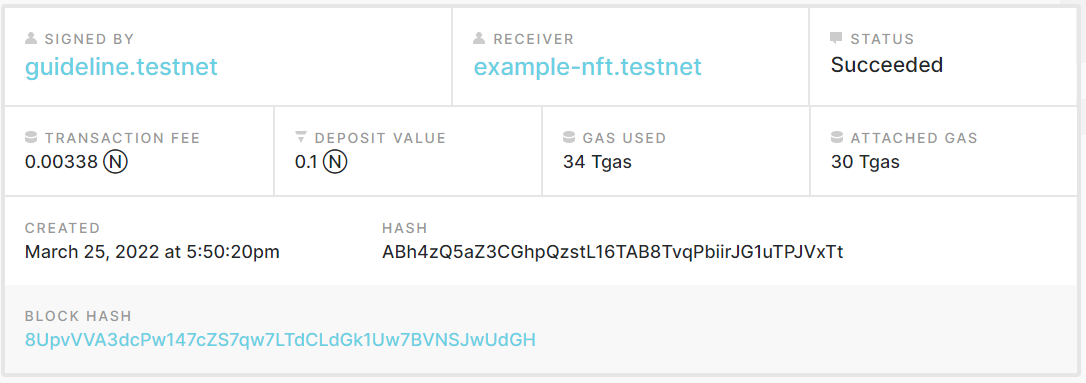

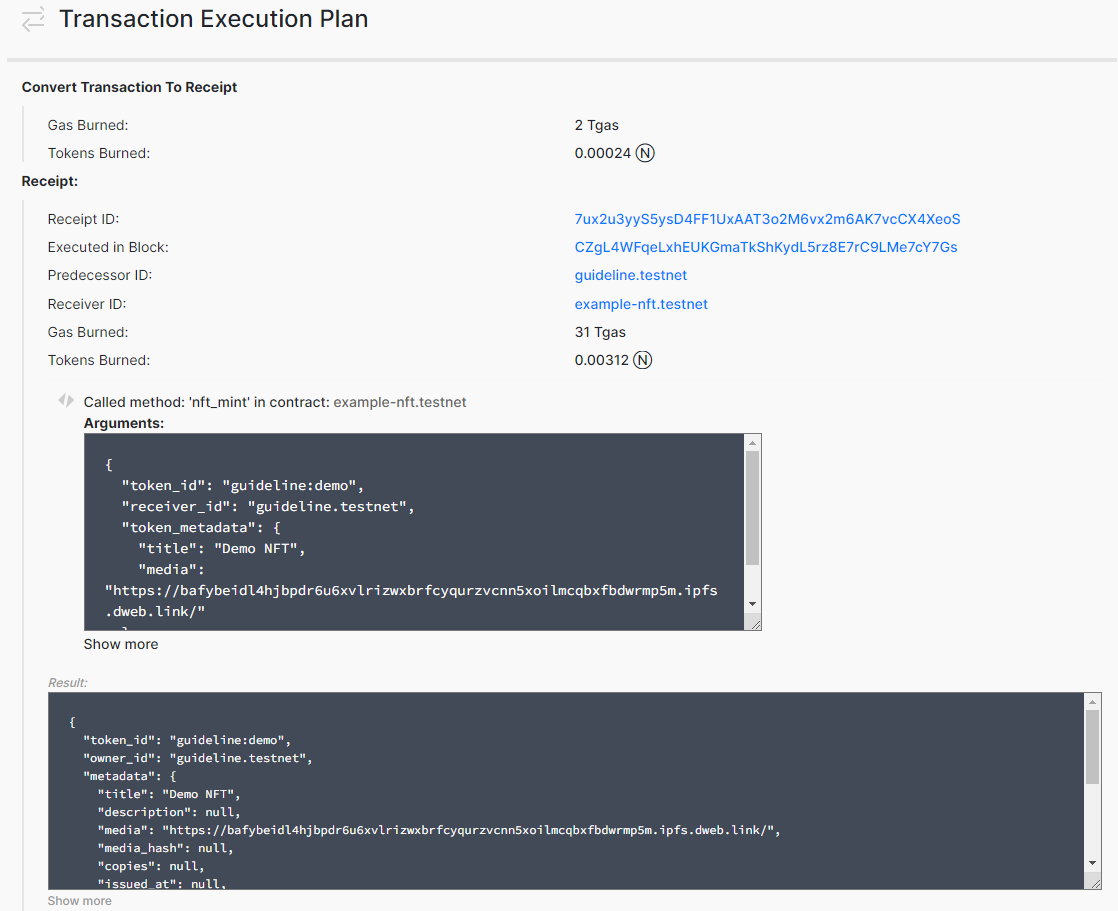

Last, but not least, blockchain transactions can be viewed using NEAR Explorer. It provides insights into transaction execution and outcome. Let’s look at one example. First of all, we can see general transaction information - sender, receiver, status. After this, we can see gas usage information: It provides insights into transaction execution and outcome. Let’s look at one example. First of all, we can see general transaction information - sender, receiver, status. After this, we can see gas usage information:

- Attached gas - total gas provided for the transaction.

- Gas used - actual gas spend.

- Transaction fee - gas used multiplied to current gas price, shows an actual cost of a transaction in NEAR tokens. Also, Deposit Value shows the amount of NEAR tokens transferred from sender to receiver. Also, Deposit Value shows the amount of NEAR tokens transferred from sender to receiver.

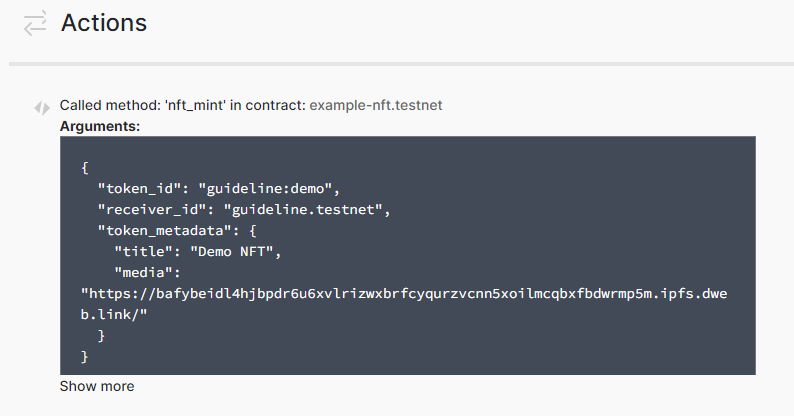

Below this, we can inspect transaction actions (recall, that transactions may have multiple actions). In this case, we have a single FunctionCall action with arguments: In this case, we have a single FunctionCall action with arguments:

At the end, transaction execution details, including token transfers, logs, cross-contract calls and gas refunds are provided. One thing that we haven’t covered yet is shown here - receipts. For most practical purposes they are just a transaction implementation detail. They are quite useful in a transaction explorer to understand how a transaction was executed, but aren’t really relevant outside of it.

Contract upgrades

During the development, and sometimes even in production, updates to a contract’s code (or even data) are needed. That’s why different contract upgrades mechanisms have been created. That’s why different contract upgrades mechanisms have been created.

While developing the contract, we recommend just creating a new account each time you need to deploy a contract (the create-account command in NEAR CLI exists for this). With such an approach, you will start with a clean state each time. With such an approach, you will start with a clean state each time.

However, once we move to a more stable environment, like testing or production, more sophisticated methods are needed. Redeployment of code is quite simple: we just issue another DeployContract transaction, and NEAR will handle the rest. However, once we move to a more stable environment, like testing or production, more sophisticated methods are needed. Redeployment of code is quite simple: we just issue another DeployContract transaction, and NEAR will handle the rest. The biggest challenge is to migrate contract state - several approaches are possible, but all of them involve some kind of migration code.

But we can take our upgrade strategy one step further. In the previous strategies, developers are fully in control of code upgrades. This is fine for many applications, but it requires some level of trust between users and developers, since malicious changes could be made at any moment and without the user’s consent (as it sometimes happens in npm world). To solve this, a contract update process itself can also be decentralized - this is called Programmatic Updates. The exact strategy may vary, but the basic idea is that the contract update code is implemented in a smart contract itself, and a Full Access key to the contract account is removed from a blockchain (via DeleteKey transaction). In this way, an update strategy is transparent to everyone and cannot be changed by developers at will.

Further reading

For a deep dive into NEAR, the following links will be useful: